With New MLB Rules, The Devil is in the Details

MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred's quest to ruin baseball continues, with contradictory and unnecessary changes.

I’ve been stewing on this for days.

I’ve been talking about how Rob Manfred is bad for baseball for years. As a reminder, this is what Manfred has already done to the game:

Limited to the number of visits players and coaches can visit the pitcher’s mound during the game.

Instituted a rule that pitchers must face a minimum of three batters or pitch until the end of an inning before being removed.

Instituted the universal designated hitter rule across both leagues;

Created rules for extra-inning games that place a runner on second base at the start of every inning beginning in the 10th inning.

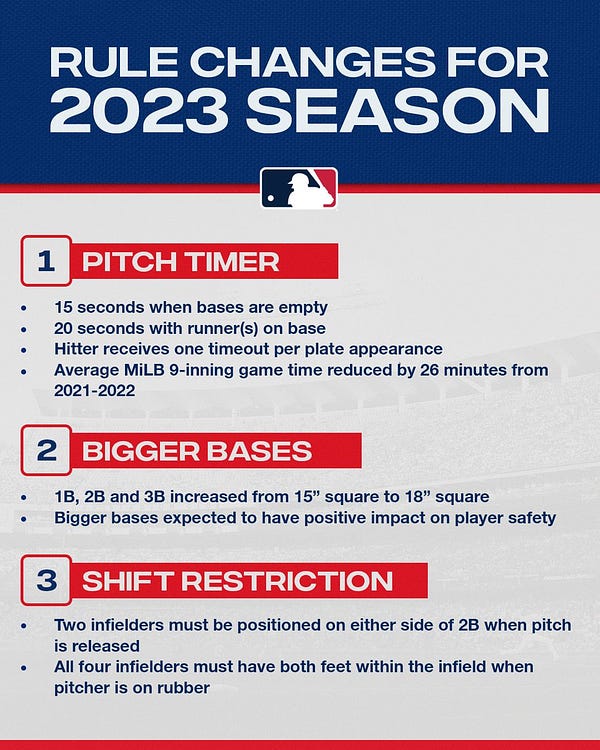

Then on Friday, we got this.

Once again, Rob Manfred has decided to absolutely mess around with the onfield product instead of addressing the issues that could adequately improve the game.

Let’s take these rules one by one:

Pitch Timer

Now, I have less of an issue with this than I do with most of the rules. As stated above, the rule would probably be fine, though I’m not too keen on the “one timeout per plate appearance” rule.

Pitchers are limited to two disengagements (pickoff attempts or step-offs) per plate appearance. However, this limit is reset if a runner or runners advance during the plate appearance.

If a third pickoff attempt is made, the runner automatically advances one base if the pickoff attempt is not successful.

So now we are limiting the number of times a pitcher can try to keep the runner from stealing bases. For guys who are fast or are great base stealers, it’s going to be an open season on pitchers, particularly right-handed pitchers who have bad pickoff moves. Can you imagine how many bases Rickey Henderson could have stolen during his career with these kinds of restrictions on pickoff moves? He’d have stolen at least another 300 bases.

But either way, what is the point of all of this? MLB says that Minor League games were shortened by 26 minutes by instituting the pitch clock. But remember that we could save nine minutes in a game just by reducing the time between half-innings by thirty seconds each.

Bigger Bases

The bases are growing from 15 inches to 18 inches. Why?

Though this can have a modest impact on stolen-base success rate, the primary goal of this change is to give players more room to operate and to avoid collisions. This is especially important at first base, where fielders have an extra 3-inch advantage to stay out of harm’s way from the baserunner while receiving throws.

This change will create a 4 1/2-inch reduction in the distance between first and second base and between second base and third, which encourages more stolen-base attempts. The bigger bases could also have the effect of reducing oversliding in which a player loses contact with the bag while sliding through it.

Baseball is a game of inches. There is no scenario that I can imagine that player safety will be increased by three additional inches on each side. The logic just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. What it will do will make stealing bases even easier; when you combine the larger base with the pickoff restrictions, it will be open season for baserunners.

Shift Restrictions

Gag me with a spoon.

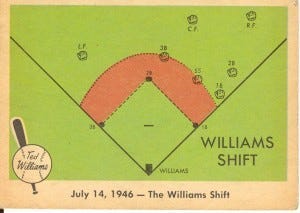

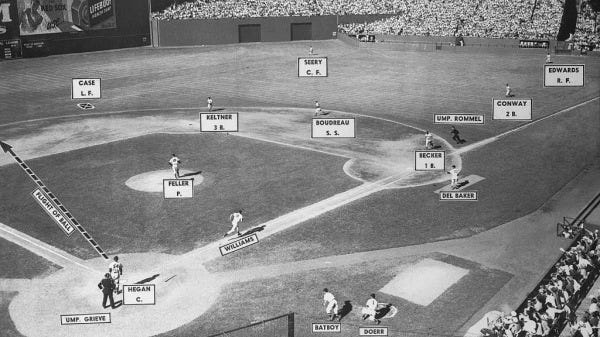

Ever hear of the Williams shift? It was employed against Ted Williams at times starting in 1946.

You’ll notice in that last picture that the shift was even more extreme than most infield shifts we see today, with the left fielder playing a deep shortstop, basically.

Williams just hit the ball the other way.

Williams finished 2-for-5, and he did the same the next day against the White Sox. According to Mike Vaccaro of the New York Post, Williams also beat the shift with a bunt down the third-base line, and Dykes soon gave up the strategy.

Williams also, after three years of flying in the Pacific for the Marine Corps, hit .342 that year, won the MVP, and led the Red Sox to the World Series.

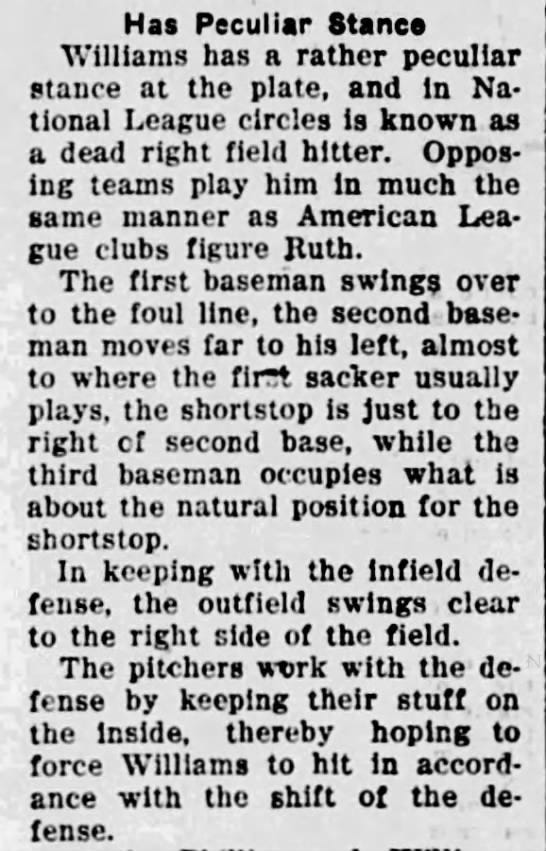

The shift of course predated Ted Williams. By more than twenty years. The shift was first used against Phillies slugger Cy Williams more than 100 years ago.

Now, I get that people use the shift more than ever due to analytics. But players beat the shift all the time.

Learning how to hit the other way or drop a bunt down the 3rd baseline is why David Ortiz is in the Hall of Fame and Chris Davis retired with two years left on his contract.

Somehow MLB’s new shift restriction rules are even more draconian than I expected:

The four infielders must be within the outer boundary of the infield when the pitcher is on the rubber.

Infielders may not switch sides. In other words, a team cannot reposition its best defender on the side of the infield the batter is more likely to hit the ball.

If the infielders are not aligned properly at the time of the pitch, the offense can choose an automatic ball or the result of the play.

This rule does not preclude a team from positioning an outfielder in the infield or in the shallow outfield grass in certain situations. But it does prohibit four-outfielder alignments.

It is absolutely surreal how in-depth these rules got into restricting defenses.

Players have played deep, sometimes on the outfield grass for years. Those positions are not necessarily related to a shift, just the fact that the opposing hitter hits the ball hard. So why stop that?

Infielders have, traditionally, not switched sides. But why should teams be restricted from doing so? Imagine in football a rule that prevented the #1 cornerback from switching sides of the field to cover the #1 wide receiving. Same energy.1

The penalty makes no sense either. The offensive team can choose a ball or the result? That makes no sense whatsoever. If the players are aligned illegally, why isn’t a dead ball called when the pitch starts, much like when a balk is called?

The new rules also, apparently, don’t preclude the five-man infield. But only in certain situations that are apparently undefined.

All of these shift restrictions do little to balance the game, and instead shifts the pendulum toward the offense without creating equitable changes to keep the pitchers ability to get the hitter out balanced.

The Bottom Line: Mixed Messages

MLB’s rule changes are contradictory. The MLB front office wants the games to speed up. But they also are creating new rule changes to increase the offense which, by definition, will extend the length of the game. What does Rob Manfred want; shorter games or more offense? Because he has created a situation that creates more offense yes. But it’s hard to say that the games will be shorter with the likelihood of more runs, more at-bats, and yes more pitching changes.

There’s nothing wrong with the damn game. And yet Manfred continues to tinker with it. Major League Baseball desperately needs a commissioner willing to scrap these rules, scrap the three-batter rule, scrap the bonus runner in extra-innings, scrap the DH, and go back to the way the game was meant to be played.

And yet outfielders are not prohibited. Not that this happens much either, but it did in 1986.